The Barbell Strategy of Travel: A Probabilistic Framework for Serendipity

I’ve been thinking recently about the underlying structure of travel.

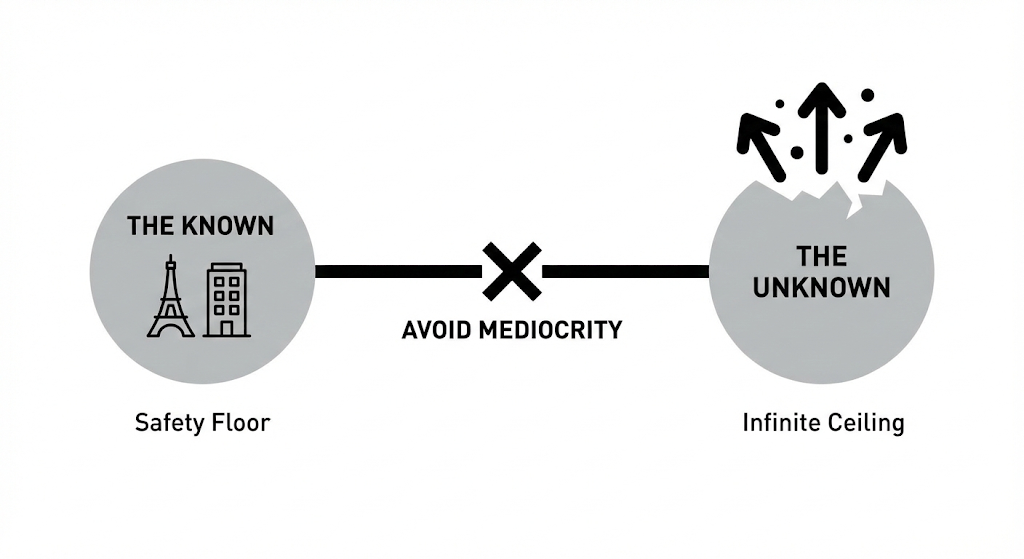

When we visit famous, well-known attractions, we are essentially engaging in an activity where the upper and lower bounds are strictly defined. A visit to the Eiffel Tower or the Great Wall offers a high “floor” (it is safe, impressive, and has good infrastructure) but a capped “ceiling.” You are there to verify information you already have, not to discover something new. The experience is “priced in.”

Conversely, going to unknown places—nameless alleyways, neighborhood noodle shops, towns without Wikipedia pages—is pure exploration. The variance is wild. The lower bound can be terrible (unsafe, dirty, boring), but the upper bound is theoretically infinite.

Intuitively, we know the second path is where the magic happens. But it is also where the risk lies.

This led me to a realization: The optimal travel strategy is an application of Nassim Taleb’s “Barbell Strategy.”

To travel well, we need a decision principle that allows us to rigorously cap our downsides (avoiding a ruined trip) while keeping our exposure to “positive Black Swans” (unexpected, life-changing experiences) infinite.

Here is the framework I’ve developed to treat travel not as consumption, but as a probabilistic convex bet.

The Theory: Beta vs. Alpha

We can map travel experiences onto financial probability distributions:

- The Known (Beta Returns): This is Consumption.

- Math: Low Variance, Concave.

- The Experience: You get exactly what you paid for. The upside is locked because the experience has been optimized for the average tourist. It is safe, but it lacks the potential for awe.

- The Unknown (Alpha Returns): This is Venture Capital.

- Math: High Variance, Fat-tailed, Convex.

- The Experience: The downside is unpleasantness, but the upside is open-ended. This is where you find the “glitch in the matrix”—the unexpected conversation, the aesthetic shock, or the moment of deep connection that no guidebook could predict.

The mistake most travelers make is staying in the “Mediocre Middle.” They visit the “Top 10” lists, the commercialized “Old Towns,” and the “Must-Try” influencer spots. These places have the worst risk/reward ratio: the soul has been engineered out (capping the upside), but the crowds and prices are high.

The Strategy: Avoid the middle entirely. Be hyper-conservative on one end, and hyper-aggressive on the other.

The Algorithm: 4 Rules for Anti-Fragile Travel

To execute the Barbell Strategy, I use four principles to protect the floor while chasing the ceiling.

1. Anchor & Drift (Physics)

You cannot take risks if you are worried about survival. You need a fortress.

- The Anchor (20% Allocation): I invest heavily in a “safety base”—a hotel in a safe, central area with great logistics. I also plan exactly one world-class landmark per trip (the “Must-See”) to ensure the trip has a guaranteed “passing grade.”

- The Drift (80% Allocation): Once the anchor is set, I abandon all other planning. The rest of the time is for random walks. Because my downside is covered (I have a safe bed and I’ve seen the main sight), I have the psychological freedom to get lost.

2. The Lindy Filter & Bio-Signaling (Selection)

How do you distinguish a “hidden gem” from a “dump” without looking at reviews?

- The Lindy Filter (Predicting Upside): Use the Lindy Effect: For non-perishable things, life expectancy is proportional to current age. If a restaurant looks run-down, has no marketing, but has been open for 30 years, its core product (the food) must be exceptional to keep it in business. Avoid the “shiny and new” places optimized for tourists.

- Bio-Signaling (Protecting Downside): Look at the locals. If they look stressed, rushing, or guarded, leave immediately. If they are loitering—playing chess, drinking tea on the sidewalk, or staring into space—the area has high “livability.” This is the petri dish for serendipity.

3. Seek Non-Transactional Interactions (The Source of Alpha)

The “High Ceiling” we seek rarely comes from scenery; it comes from connection.

- The Signal: Avoid anyone who wants to sell you something (transactional). Run toward scenes where you are irrelevant.

- The Goal: Stumbling upon a local wedding, a university campus debate, or a park mahjong game offers high “narrative yield.” These are the moments you remember forever because they were unscripted violations of your expectations.

4. The Stop-Loss Option (Risk Management)

The biggest risk in exploration is not losing money; it is losing time.

- The 15-Minute Rule: If I enter an unknown area or restaurant and the sensory input (smell, light, vibe) feels “off,” I leave within 15 minutes.

- Reject Sunk Costs: It doesn’t matter if I took a 40-minute taxi to get there. Staying in a bad situation caps my upside. Leaving immediately buys me a ticket for another random roll of the dice.

Summary: The Traveler’s Portfolio

If I were to treat my travel itinerary as an investment portfolio, the allocation looks like this:

- 20% Government Bonds (Safety): Great sleep, top-tier logistics, and one unmissable landmark. (Goal: Preservation).

- 0% Corporate Junk Bonds (Mediocrity): Mercilessly delete all tourist streets, influencer hotspots, and generic “Must-Do” lists. (Goal: Avoid Boredom).

- 80% Venture Capital (Discovery): Random walks, high sampling rate (walking vs. driving), and following the “Lindy” signal into old, unpolished places. (Goal: Infinite Upside).

Traditional tourism is about consuming certainty. This approach is about investing in convexity. You accept small losses (a bad meal, a wasted walk) as the price of admission for the infinite upside of the unknown.